|

|

|

|

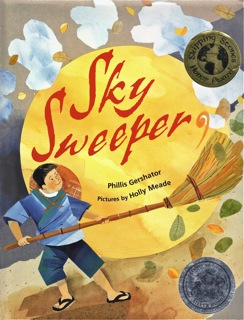

Sky

Sweeper

illustrated

by Holly Meade

Melanie Kroupa Books

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007

|

*Starred

review,

Kirkus

*Parents

Choice

Silver Award, 2007

*S&P

Book

Awards:

Best Spiritual Books of 2007

*Starred

review,

Library Media Connection

*Skipping

Stones

Honor Award:

Multicultural and

International Books, 2008

*Lupine

Picture

Book Honor Award, 2007

*Capitol

Choices Noteworthy Titles for

Children and Teens, 2008

|

| From

the book jacket: |

Can a

single flower say more than

words?

Young

Takeboki needs a job, and the

monks in the temple need a

Flower Keeper--so Takeboki sets

to work. It’s the Flower

Keeper’s job to sweep up the

springtime plum and cherry

blossoms in the temple garden.

As the seasons change, Takeboki

continues to find pleasure in

doing his job well--sweeping up

flowers and leaves and snow--and

then creating swirling worlds of

his own in the gravel and sand

of the temple garden.

Friends

and family ask him: Shouldn’t

you get a better job? Wouldn’t

you like to see more of the

world? Takeboki can’t answer

those questions. All he knows is

that as the seasons shift, each

one as beautiful as the last, he

is happy.

Luminescent collage

illustrations created from

delicate Japanese papers bring

to life this thought-provoking

parable that, with its Buddhist

sensibility, has much to say

about work, wisdom, and the

possibility of discovering a

world of unending delight in one

small garden.

|

| A

little about the book: |

When I read about an old-time job in

Japan, that of Flower Keeper, the

words and image stayed with me, and a

story began to unfold and evolve over

the years. I was helped by my readers,

especially Holly Meade, who had a

vision of how the text would work as a

picture book and how it could be

simplified to focus on its most

important messages about life, work,

and happiness.

It

makes me happy when I look at Holly's

beautiful artwork (her site:

http://reachroadgallery.com/ )–– and

it makes me happy to hear the

different “lessons” people draw from

the Flower Keeper's story.

The story might touch off a classroom

discussion, an exploration of

philosophical questions such as: What

is play? What is work? What makes a

good life? And of course, What makes a

person happy?

When I read Sky

Sweeper to

Elisabeth Anderson’s class at Antilles

School in St. Thomas, her fourth

graders responded with a group poem

about happiness:

WHAT

MAKES ME HAPPY?

by Class 4A

What makes me

happy?

Reading gives me a good feeling

Basketball – I like to get the ball in

the hoop

My PS2 – it’s electronic!

What makes me

happy?

Sailing – it’s my sport

Gliding across the water

Traveling around the world

Going sight-seeing

Swimming

I like to be under water

It’s nice and warm

What makes me

happy?

Gymnastics - being on my hands

instead of my feet

Golf – I’m good at it

I like to swing my driver

My Xbox – ‘cause I can control

the person in the game

What makes me

happy?

Playing with my kitty

I roll up a tin foil ball

and she pounces on it

My parakeet--teaching it to sing

Sometimes it chirps

loudly and annoyingly

but sometimes it chirps

sweetly

Football – I like to score

What makes me

happy?

Kick ball

I like to kick the ball

Jumping in the pool

feeling the freezing

water

Sleeping - I can be unconscious

I don’t know what’s going

on

If something bad happens,

I won’t remember

When I’m awake -

acting

expressing a

character

What makes me

happy?

Holidays

You get to be with your family

You get to get to spend time with them

You love them

And they love you.

And then someone in the class asked,

“What makes us

ALL happy?

And his classmates answered,

“Eating!”

In the

classroom, the Flower Keeper's story

might also lead to an exploration of

Japanese literary forms: haiku and

haibun. Writing haiku is already a

popular activity, but I’m hoping

children will be encouraged to write without

the seventeen syllable rule as an

absolute. In fact, seventeen syllables

create a poem that is often too long

and wordy to be called a haiku. The

Haiku Society of America adopted this

definition:

1) An un-rhymed Japanese poem

recording

the essence of a moment keenly

perceived,

in which Nature is linked to human

nature.

It usually consists of seventeen onji

[sound units].

2) A foreign adaptation of 1, usually

written

in three lines totaling fewer than

seventeen syllables.

Most

important of all is the “haiku

spirit.” In her terrific teacher’s

manual, The Haiku Habit Workshop,

Jeanne Emrich writes: “The haiku way

is just to say it--simply. Written in

a very direct manner, haiku tell the

who, what, where, and when of the

moment as the author perceived it

through his or her senses. The result

of such a concrete description is that

the reader feels as if he or she also

is having the experience. And because

commentary is kept to a minimum, the

reader is free to come to his or her

own conclusions about what the

experience means....”

Haibun is

prose--a story, impression, incident,

description--which includes haiku. Sky Sweeper

concludes with a haiku by Moritake,

one of the most famous haiku in

Japanese literature. It evokes the

garden setting for me, and the

mysteries, delights, and surprises one

encounters in a garden. If one wishes

to seek out connections, Moritake’s

haiku relates to the story through the

image of the blossom. Blossom is a

“seasonal word,” which many haiku

contain to indicate time and place. It

represents spring, a time of birth and

rebirth, and a connection to the

Flower Keeper’s job as well.

The

butterfly, a creature of fragile

beauty, with a magically dramatic life

cycle, also symbolizes life’s

preciousness--and transience. Is it

any wonder that, for some Japanese,

butterflies represent the souls of the

dead?

I like to

think that the Sky Sweeper lives on,

if not in the butterfly, then in the

spirit of the young gardener who

follows in his footsteps and shares

his knowledge and his happiness.

I would also

like to think, along with caring for

the temple garden, that the Flower

Keeper cultivated “the seeds of

compassion," as Thich Nhat Hanh put

it.

When I

was working on Sky Sweeper,

my daughter introduced me to the

writing of Thich Nhat Hanh, a Zen

Buddhist monk who has become one of

the truly spiritual voices of our

time. His teachings promote the

attainment of peace for ourselves and

for the world. For example, by not

responding to anger with anger, we can

create the possibility of turning our

enemies into friends. Imagine if we

lived in a world governed by the

teaching of non-violence!

In an article

in Yoga

Journal (Sept./Oct. 2003),

Thich Nhat Hanh describes

Buddha’s transformation of the

arrows of Mara, the Evil One, into

flowers. Transforming negative

emotions into positive ones, he

writes, will transform ourselves and

others: “You soon see that arrows shot

at you come out of other people’s

pain. You do not feel injured...;

instead you have only compassion....”

He acknowledges this may be difficult

but teaches that, in this way, “We can

all make flowers out of arrows.”

To those who do not

recognize the value of his work and

feel he should take a less

“lowly” path in life, the Flower

Keeper responds not with anger but

with empathy and good humor, a fitting

response for one who will ultimately

smile with the inner peace and

contentment of Buddha himself, the

same Buddha who smiled in his flowery

victory over Mara.

|

| From

the reviews: |

“Infused with a Buddhist sensibility,

written in clear, minimalist language,

accompanied by rich, organic

illustrations and culminating in a

haiku by Moritake, this is an

origiinal fable not to be missed.” Kirkus,

starred review.

"This is a complex, challenging story.

Children will need help connecting

Gershator’s poetic, often

Zen-influenced messages about

Takeboki’s sense of purpose and

personal reward; his death adds even

more weight to the story. But Meade’s

beautiful collage illustrations of the

earthly garden and glorious afterlife

greatly enhance the story’s

accessibility and will help kids get

closer to the text’s religious and

philosophical themes." Booklist

"Only after the old man's death do the

monks realize that his humble work has

nourished their own serenity. Takeboki

himself graduates to a perfect heaven

(for him): now he sweeps the sky. As

Gershator explains in a note, her

story celebrates the rewards of

meaningful work as well as the

artistry of Japanese gardens. Meade's

mixed-media illustrations (collage,

paint, delicate line) intimately

depict the dedication to a

simple-seeming task that is, in truth,

an art." Hornbook

“The illustrations provide a

bit of foreshadowing, incorporating

the figure of another smiling boy, the

future Flower Keeper, in later

scenes.... Nicely constructed for

reading aloud, this quiet story has a

satisfying progression that might

prompt reflective discussion.” School

Library Journal

"As Gershator's (Rata-Pata-Scata-Fata)

resonant, lyrical tale opens,

young Takeboki takes a job as a Flower

Keeper for the temple monks. Though

his task is to sweep up the fallen

plum and cherry blossoms in their

garden in spring, the conscientious,

content worker continues sweeping

through the other seasons--and many of

them....Created from Japanese papers,

Meade's (Hush!) richly

textured, luminous collage

illustrations are as simple and

graceful as Gershator's narrative.

Like Takeboki's, theirs is a job well

done." Publishers Weekly

"It is a beautiful story in

both text and illustration. An

intriguing range of paper textures was

employed in creating all the collages

where one finds children playing and

people working. Two kinds of

Japanese/Buddhist gardens are

represented in the mixed-media

illustrations: the Hill-and-Pond style

garden and the Dry Landscape garden.

Due to the sophisticated theme, this

will find its greatest audience among

older children and young adults. It is

a story that would generate a lot of

discussion with middle and high school

students on a career day."

Children's Literature

"'Our age,' wrote Simone Weil

just before her death in 1943, 'has as

its own particular mission, or

vocation, the creation of a

civilization founded upon the

spiritual nature of work.' Yet today

children grow up with few models of

individuals who love their jobs and

try each day to do them to the best of

their ability. That's why this

inspiring beautifully illustrated book

by Phillis Gershator is so welcome." Spiritualityandpractice.com

The serenity of a Japanese temple

garden is captured in airy watercolor

and collage in this tribute to the

sustenance that is found in work and

beauty.... Each beautifully composed

page glows with clean color and the

delicate prints of origami paper.

Takeboki's gentle soul is central both

to the pictures and the spare text.

This is a satisfying and

thought-provoking book to share.

Highly recommended. Library

Media Connection, starred

review

Art by Holly Meade

|

|

|

|

|